Daglingworth Resettlement Camp: Story of a Polish Resettlement Camp near Cirencester in the Cotswolds by Edward Lender

All paintings by Anna Lender

Daglingworth Camp was built in 1940 as a military hospital for the wounded American servicemen who fought in the Second World War. At the end of the war in 1945 it was no longer required, and the American soldiers returned to the USA.

The Polish Army fought bravely with the British and American forces in the Italian campaigns. They were successful in the Battle of Monte Cassino and had suffered large losses. The Polish Navy played a vital role in protecting the British coast, the destroyer ORP Błyskawica patrolled the sea around the Isle of Wight. Brave Polish Pilots flew fighter aircraft in the Battle of Britain protecting Britain.

When the war finished many Polish soldiers felt they were badly let down, humiliated by the Allies, given the label of displaced persons, and placed in the abandoned army camps with disintegrating Nissen huts and barracks. The camps were renamed Displaced Persons Camps.

One of many of these camps in Gloucestershire, Daglingworth Camp was on a hill about two miles from Cirencester along the Gloucester Road, above the charming Daglingworth village in a beautiful part of the Cotswolds. Its function was that of a transit camp. The soldiers’ wives, children, mothers and fathers, sisters, brothers, and other family members had suffered six years of separation; having lived in camps in Africa, India and the Middle East and having subsequently travelled for weeks on trains and troop ships, across the Indian Ocean, through the Suez Canal and the Mediterranean Sea, they finally arrived in Southampton. They were then transported by army trucks to Daglingworth Camp to be reunited with the soldiers.

The plan was to bring the families together, get them registered and move them on to other camps around the UK as quickly as possible. The registration process did not go as smoothly as the authorities had expected. They were overwhelmed with thousands of families arriving day and night. People were crammed together into the huts, where there was no privacy. The place was unsuitable for families. They were exhausted, traumatized, and sick. Many needed medical attention. The journey and the cold climate were too much for some, and they were taken to special Polish hospital camps. Sadly, some died. It was especially sad when mothers died, leaving the children orphaned. The Red Cross and the good people of Cirencester would come to the camp with donations of clothes and toys for the children. All was gratefully received. These gifts brought great joy especially to the children, who would eagerly look forward to the next delivery. There was great excitement when the delivery arrived; as the camp became less crowded and more settled the families were ready to move on with their lives. There was a major drawback, however, because the authorities could not decide if the camp was a temporary place or if it was to be a permanent residence for the foreseeable future.

Finally, a decision was made. Maintenance teams arrived and started a programme of repairs. A large part of the camp was beyond repair and was fenced off and out of bounds to the residents. The habitable barracks and huts were divided into family units, with cooking ranges, and coal bunkers placed outside. Leaking roofs were fixed, glass was replaced in the steel framed windows and the walls were painted. Each unit had a front door and a number.

Families back home in Poland had also experienced the pain of the upheaval created by war. They were moved from the East to the west of Poland. Now through the Red Cross organisation people were able to find each other. Having an address, they were able to send letters and photographs to their families back home. Receiving letters and photographs was a great help in their recovery from their painful and traumatic experiences.

Polish women were homemakers. Skills of homemaking were passed down through generations, from grandmothers to daughters and from them onto their children. They took great pride in providing for their family, teaching their children baking and cooking; teaching their children about Polish history, cultural and traditional celebrations. the men had already demonstrated the values of courage and honour passed on to them by their grandfathers and fathers. The homemakers were now able to start their craft of homemaking. Not so much with a blank canvas, more realistically in a blank shed, with bare floors and walls and blackout curtains in the windows. The furniture consisted of a small wooden table – the size of a card table – and four folding chairs, iron framed beds and mattresses and army blankets, as many as you needed.

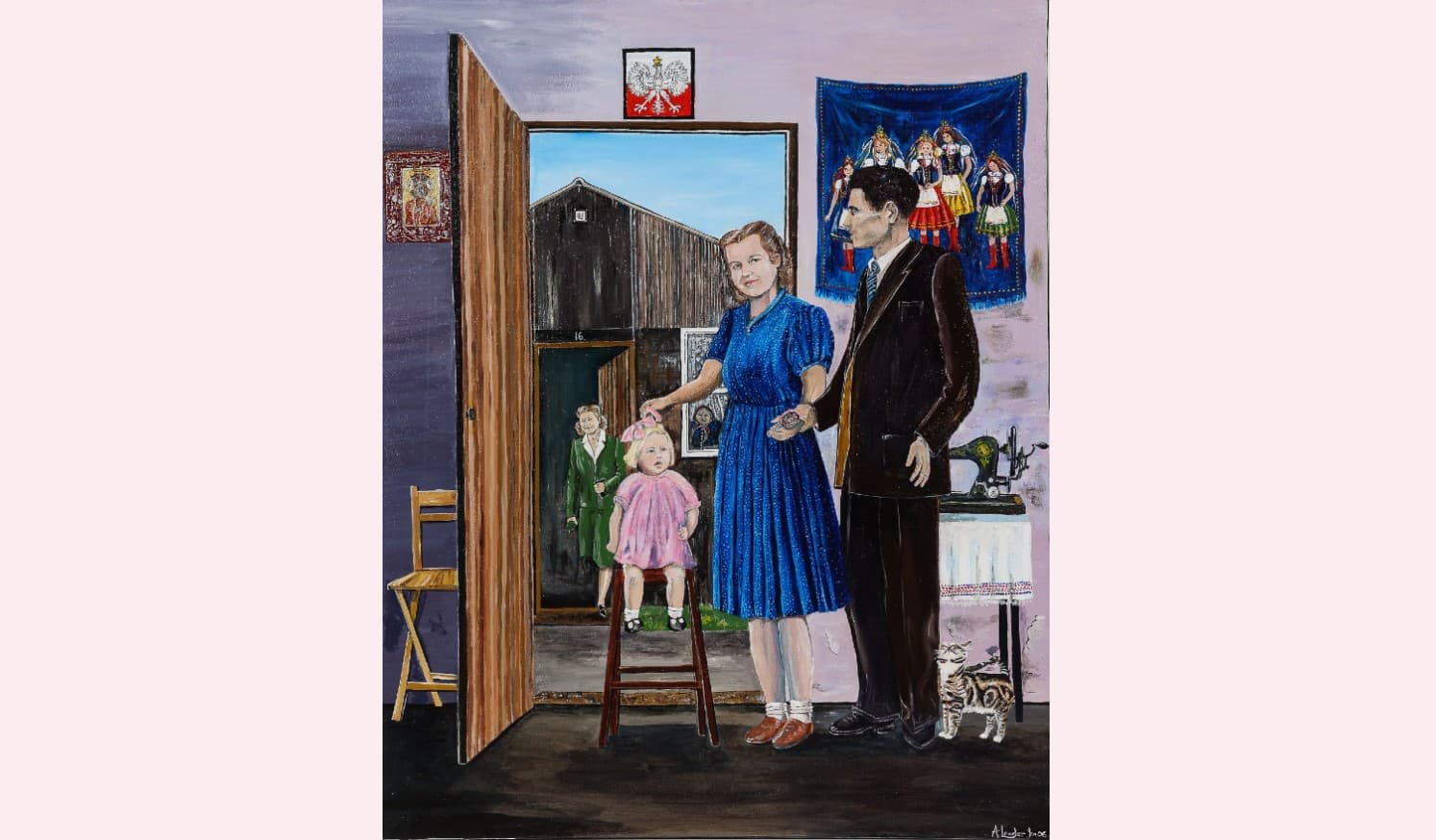

Painting 1 by Anna Lender. Anna at the age of two sitting on a stool at the front door of the hut. Her mother is adjusting a ribbon in her hair; her mother died when Anna was three years old. Anna’s father and stepmother are also in the painting.

The communal mess hall was being phased out and cutlery and kitchen equipment became available. They missed eight years of freedom to provide home cooked meals and a home for their family. There was a lot of catching up to do. Their pride and dignity may have been dented, but they were not going to be beaten.

An essential part of a Polish household is to provide a clean and tidy front room to welcome friends and family to celebrate family occasions like Christenings and Christmas. With a bit of ingenuity, the army blankets were used to separate an area to make a front room. Fabrics were required to make tablecloths, net curtains and decorative wall hangings. On Sundays after Mass there was the information forum. Word spread that there was a shop in Cirencester that had netting material essential for net curtains as well as for making dresses for the young girls going to First Holy Communion, babies’ christening sets, and brides’ wedding veils and dresses. On Saturdays women organised shopping trips, walking down the hill to town, getting fabrics. The shop became known as the French shop as it provided all the fabrics needed for homemaking – bed linen and all essential fabrics for dress making, embroidery and knitting wool. Shopping trips to Cirencester for food and clothes, restricted of course by the availability of ration coupons, were now a feature of life.

Painting 2 by Anna Lender. Anna waiting patiently for her turn to go on the children’s swing.

Traders came to the camp on a Friday to sell provisions and fresh meat in the form of hens and rabbits. The milkman arrived each morning to be met by boys eager to help with deliveries, in return for a small bottle of milk as payment. Farmers came with farm products, potatoes, fruit and eggs. Once a week the coal merchant arrived with very dirty bags of coal. A regular hourly bus service from Cirencester to Gloucester and back stopped at the camp gates. The more adventurous shoppers travelled to Gloucester to buy a winter coat from Debenhams at Christmas time. The Polish Father Christmas (St. Nicholas) always had presents for all the children.

Daglingworth Camp was like a Polish village in the Cotswolds, where people maintained Polish culture through its traditions and religion. Since the year 966 Poland became a Christian country. The Roman Catholic faith is the predominant religion. ‘Poland will not perish as long, as we are alive’ were the words of the Polish national anthem. One of the large Nissen huts was blessed by the priest and functioned as a church. Regular Sunday Masses were held. Prayers were said for the soldiers who had died in the war and the people who perished from disease and malnutrition; there were also thanksgiving prayers for people who had survived. Poland had a special devotion to Matka Boska (Mary, Mother of God), and daily prayers of devotion were said in church with the Rosary, mainly by the Polish women.

Painting 3 by Anna Lender. Children dressed in donated clothes on a day out in Cirencester Park woods playing a game called ‘chodzi lis’. The game is about a fox – the English equivalent would be ‘What’s the time Mr. Wolf?’

Traders came to the camp on a Friday to sell provisions and fresh meat in the form of hens and rabbits. The milkman arrived each morning to be met by boys eager to help with deliveries, in return for a small bottle of milk as payment. Farmers came with farm products, potatoes, fruit and eggs. Once a week the coal merchant arrived with very dirty bags of coal. A regular hourly bus service from Cirencester to Gloucester and back stopped at the camp gates. The more adventurous shoppers travelled to Gloucester to buy a winter coat from Debenhams at Christmas time. The Polish Father Christmas (St. Nicholas) always had presents for all the children.

Daglingworth Camp was like a Polish village in the Cotswolds, where people maintained Polish culture through its traditions and religion. Since the year 966 Poland became a Christian country. The Roman Catholic faith is the predominant religion. ‘Poland will not perish as long, as we are alive’ were the words of the Polish national anthem. One of the large Nissen huts was blessed by the priest and functioned as a church. Regular Sunday Masses were held. Prayers were said for the soldiers who had died in the war and the people who perished from disease and malnutrition; there were also thanksgiving prayers for people who had survived. Poland had a special devotion to Matka Boska (Mary, Mother of God), and daily prayers of devotion were said in church with the Rosary, mainly by the Polish women.

Painting 4 by Anna Lender. Anna is one of the flower girls in the Corpus Christi Procession. Four temporary alters were put up around the camp by social groups like the Scouts and the Rosary prayer group. The procession then stopped at each alter for prayers.

Painting 5 by Anna Lender. The Corpus Christi Procession in the camp. Cirencester Parish church in the background.

There were hundreds of single young soldiers who were now civilians and left on their own having no family in the UK. They had to be helped. Families gathered them up for Polish home cooking and friendship. They often became part of the family. They were young eligible men, so the next step was to look for a wife. Today they would have registered on dating sites to find love. Back in the day, however, those that were not successful finding a wife on their own were in the safe hands of matchmakers eager to help. There were lots of religious marriages in St Peter’s Roman Catholic Church in Cirencester. The weddings were celebrated in a traditional Polish style in the camp. The large, now empty, Nissen huts were ideal for wedding celebrations with dancing, singing and loud music. No one complained about the loud noise as the nearest neighbours were over a mile away.

From the beginning there was an affinity between the Polish arrivals, the people of Cirencester, and the surrounding area. There was a mutual respect and understanding that it was the war that brought about the plight of the Polish people and that led to their present situation; and that they could not get back to their homeland. Many local people helped them to settle and start a new life in the UK. They found that living in the beautiful Cotswolds – with rolling hills, golden cornfields and flowering meadows divided by stone walls, narrow roads and hedges covered with rambling roses and blackberry bushes, birds singing and darting about, farm paths meandering through fields and valleys – was ideal for long Sunday afternoon family walks. Picking wild berries and hazelnuts, and foraging for mushrooms in Cirencester Park woods in the autumn went a long way in helping families to settle in the UK.

Painting 6 by Anna Lender. A kestrel hovering over the Cotswolds.

The Polish mother’s mantra was that children must be fed, clothed, and sent to school to be educated. The school in the camp had a register of all the school-age children. They were all given lessons in Polish. The Gloucestershire education authority worked together with the camp school and the Polish priest to enable the children who could speak some English to attend the Stratton Church of England Primary School. This was a bold move by the education authorities and gave the opportunity for the children to progress onto the Cirencester Grammar School and also to the Cirencester Deer Park Secondary Modern School. Some went on to further education, did very well, and qualified as teachers, doctors, nurses and engineers. The Our Lady’s Convent Roman Catholic High School in Cirencester provided education for girls only.

Men and woman were finding employment with engineering companies in Cirencester, and in farming, building and service industries around Gloucestershire. The camp maintenance men had the job of keeping the boilers stoked day and night, and keeping the hot water system working. Not only did they win the gratitude of the women of the camp, but they deserved a medal for their work. The team of men cycled each day from Chedworth and back to do their job and keep the hot water system working.

It was now the summer of 1955 and there was something in the air. American bombers were in operation from the RAF Fairford air base and the Cold War had just got warmer. American servicemen were back in the Cotswolds. Cirencester Carnival and Fair were held in a field in the town. It was a wonderful day. On Sunday after Mass a spontaneous decision was made to have a day out at the fair. Packed lunches were put together and most of the families, hundreds of people – men women, and children – walked down the hill to the fair. People living along Gloucester Road came out of their houses to see what was happening. Where were the Polish people going?

That day marked the turning point. Soon families started moving out of the camp, finding housing and jobs in the towns like Stroud, Dursley, Gloucester and Cirencester, and mostly moving to Swindon where a small Polish community had already been established and where housing and work was available.

Saturday nights in Cirencester were full of life. People from the villages were coming to have a great night out. Hundreds of American servicemen came to enjoy the hospitality of the town. In the pubs the skittle alleys were turned into music and dance venues. A burger bar and a milk bar opened in the town.

Rock and roll had arrived in the Cotswolds. The most exciting time was in October when the Mop Fairs came to town. The marketplace was filled with excitement. Flashing lights, music, the thrill of fair rides, bumper cars, Waltzer, octopus, carousel, and Helter Skelter.

There were now less people in the camp – it was drab, the huts were falling apart. Only a few lights flickered in the night. The camp was shutting down. By the 1960s most of the people had moved out and the camp closed. Later it was demolished, and the field where it stood returned to farmland.

The Romans came to the Cotswolds and left a straight road from Cirencester to Gloucester. Much later hundreds of Polish people came and lived next to the road. They took away wonderful memories of the beautiful countryside and made lifelong friendships. They then left leaving no trace of having lived there.

My wife Anna is an artist. We both grew up in Daglingworth Camp, and we got married in the 1960s. But that is another story. Paintings by Anna of childhood memories growing up in Daglingworth Camp tell her story.

Painting 7 by Anna Lender. Poppies in a field of rye.

Special thanks to Waldemar Januszczak and Dr Marta de Zuniga for making the publication of this material possible.