Feliks Topolski RA – Chronicler of the 20th Century by Lucien Topolski

I never met my grandfather, Feliks Topolski, but his presence has surrounded my entire life. It was his eye and the sketches he had included in his fortnightly Topolski’s Chronicle that introduced me to the important political and cultural figures, events, places and movements of the last century; Martin Luther King, Mahatma Gandhi, General Douglas MacArthur; Laurence Olivier, Bob Dylan, Allen Ginsberg; Chicago, Havana, Bergen-Belsen; Punks, Hippies, Black Panthers, Maasai and the Viet Cong.

It was wandering the maze of his 600ft long, 20ft high Memoir of the Century that dwarfed me in the past in dashes of glorious colour and figurative impressions, yet within it all was an impression of history as the continuous flow of lived experience. The names and places which cropped up in conversation were not distant ideas or events, but tangible links to the past, tied together through Feliks’ own lived experience. His work instilled in me an appreciation for history not only as a means of making sense of the path to the present, but also as vital in processing our passage into the future.

From his birth in Poland in 1907 to Jewish, albeit atheist, parents, he was encouraged in his art by his mother. His father was an actor and had been imprisoned in 1905 for his part in promoting revolutionary theatre. By the time he left Poland to tour Europe in 1933, he had little tying him to his birthplace. Perhaps this independence is what gave him the confidence and freedom to travel, moving with the ease of the curious stranger amongst people great and small, always seeking the new. Arriving in London in 1935 on commission to document the Silver Jubilee of George V for a Polish magazine, Wiadomosci Literackie, Feliks fell in love with the city. Its glorious anachronisms, formalities and dress as well as the class distinctions, manners and accents enchanted him. He found the vibrancy of the city to be unlike the rest of “drab” Europe and his work was quickly found to be in high demand. His delicate, ironic sketches soon appeared in Vogue, The New Chronicle, and, in the brief career of Graham Greene and Evelyn Waugh’s Night and Day alongside regulars like Aldous Huxley and John Betjeman. George Bernard Shaw, a personal friend, described Feliks as ‘the greatest impressionist in black and white’, featuring his illustrations in several of his play texts on publication, including Pygmalion, Geneva and In Good King Charles’s Golden Days.

George Bernard Shaw with Feliks, Marion and Baby Daniel. Topolski Trustees

When war was declared, Feliks, an officer in the Polish reserve from his days on military service, was unable to return to his regiment. Instead, he became an official war artist for both Britain and Poland, and London Picture Post correspondent, traveling extensively throughout the war. He reported from London in the depths of the Blitz, incurring an injury on his painting arm after being caught in a bomb blast; he was on the first Arctic Convoy in 1941, traveling to Archangel, Moscow and beyond, publishing a book Russia in War, in 1942; he was in Africa, Iran and the Middle-East; the Burmese Jungle and India, where he shadowed Gandhi, then to Chunking to visit Chiang Kai-shek’s wartime seat of government. He was with the troops pushing up through Italy, and then Bergen-Belsen concentration camp where he also took photographs, unusually, as he thought the apocalyptic scenes he sketched wouldn’t be believed at home.

The drawings and paintings from this period are amongst his most powerful work. Germany Defeated, acquired by the Tate in 2016, has the full chaos of the end of the war in terrifying dramatic display. Emaciated concentration camp survivors in striped uniforms, a Caesar in sad laurels atop a German Panzer tank returning from Belsen. Berlin, the failed imperial metropolis, aflame as Allied and Soviet troops jostle for prominence in front of collapsing buildings, echoing the colosseum. In another, Chiang Kai-shek’s nationalists flee the mainland in a winding refugee trail. Or else the arrival of a procession of exiled Polish refugees into Uganda, observed by their African hosts in a little remembered episode of the war. In two monumental theatrical portraits, Laurence Olivier reverberates in role as both Hotspur, defiant in the final days of the war, and Oedipus’ anguished blood-curdling cry. ‘As an artist’ he writes, ‘I was welcomed in the intellectual circles of Moscow. I think I saw, therefore, more than many other visitors.’ This kind of broad access, from tramp to professor, soldier to government, shaped his travels and he saw, I dare say, more facets of the war than almost any other.

Feliks Topolski, Germany Defeated, 1945, oil on canvas, Tate Britain.

The war had solidified his reputation as an illustrator of repute. In 1950 Topolski was invited by Jawaharlal Nehru to attend the Independence Day celebrations in a young India. His government had bought Topolski’s epic painting The East, which now sits in the Rashtrapati Bhavan in New Delhi. Based on his travels during and after the war, Gandhi’s assassination fills the centre of this monumental piece. The trip took him around India, then onwards throughout South-East Asia, Japan and over the Pacific to Hollywood and New York.

Feliks and Marion in their Little Venice Home and Studio.

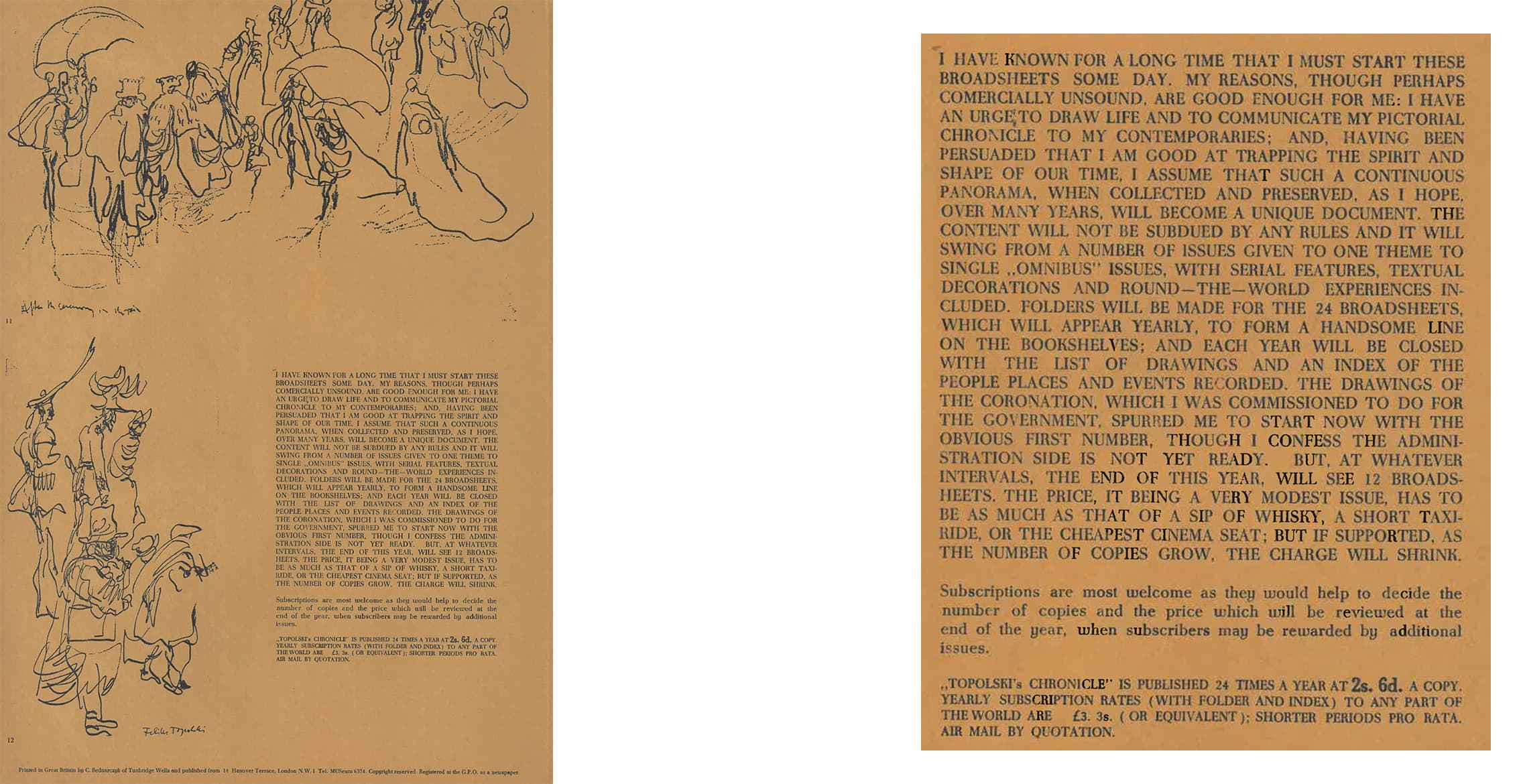

In 1953, Feliks was commissioned by the British government to document the Queen’s coronation, his eye falling equally upon the extravagant finery of the procession as it did on the street sweepers and republican ‘dissenters’. His absolute commitment to objective observation is evident in the holistic documentation of the entirety of the event, warts and all. With the sketches that made up the commission, Feliks was spurred to begin the publication of his Topolski’s Chronicle. A fortnightly collection of his best drawings, circulated to subscribers around the world, he described it as the result of his ‘urge to draw life…having been persuaded that I am good at trapping the spirit and shape of our time’. Although ‘commercially unsound, costing just as much as ‘a shot of whisky, a short taxi ride, or the cheapest cinema seat, the project was a means of expressing the ultimate purpose of his work, to build a continuous socio-cultural panorama that would, once compiled and preserved, provide a unique historical document. Running consistently until 1969, it is an unparalleled exercise in reportage, ‘bearing witness’ to some of the most important events and figures that defined the 20th century.

Elizabeth II Coronation drawings from the first Volume of Topolski’s Chronicle published in 1953, including his artistic manifesto behind establishing it

This same motive is what lies behind the Memoir of the Century, that long abstraction of dreams and memories, building a whirlwind tour of the century through his eyes. Pulling from the drawings and paintings he’d made throughout his career, it wound its way underneath a couple of railway arches on the Southbank. He had managed to acquire a studio several arches down in 1951 during his involvement with the Festival of Britain, celebrating a new chapter for the nation following the war, and for which he contributed an enormous painting, The Cavalcade of the Commonwealth. Starting with his birth, the Memoir passes through 1930s Paris, the war, the independence of India, Mao’s China, the Black Panthers; the list goes on. He continued to paint it right up until his death, and, as a true chronicle, it was never meant to be finished.

His style is timeless and immediately recognisable. Prince Philip, writing that ‘Topolski seemed the obvious choice to memorialise the Queen’s Coronation procession’, wisely gave him free rein to do so in 1959. The Coronation Mural has since adorned the walls of Buckingham Palace, using his earlier drawings to depict the coronation from the procession in the streets, to the ceremony in the abbey in 100ft of continuous energy and movement. The work is typical of his humour and wit, his impassioned yet accurate lines appearing chaotic to the untrained eye. 14 panels of ‘explosive colour, whirling lines, and bold, emotive, pictorial passion dominate both walls of one of those seemingly endless galleries’. Philip’s trust in Feliks’ vision may have produced a work he hadn’t expected, but it is undoubtedly unique and testament to Britain’s new relationship with the world that Elizabeth’s reign oversaw.

Feliks’ critical presence at the centre of so many of the significant events of the 20th century cements his place as one of the great artists of modern times. It is a constant source of joy to be able to explore and share his work with others, and developing his name for a new generation of artists. I find myself discovering new aspects of his work almost every time I put myself in front of a piece I thought I had already understood. Recently, assessing the Irish section of the Memoir with friends visiting from Dublin, awash with the green, orange and white of the tricolour, we discovered several figures and pondered over the historical context within which they sat. Was that blood raining down onto the gravestones in the cemetery grounds? Were they the graves of the hunger strikers? And was that screaming figure reproduced from an I.R.A. poster my friend had seen in a Republican pub in Dublin? All of it sparked conversation, thoughts, an exchange of ideas. We learnt about one another as we looked back at the past from our own distinct perspectives. The world Feliks saw and documented lives on, we are not isolated from it. His work reminds us that we are products of our past, and it is his talent to make us feel it so.

Photographs of Feliks Topolski from the Topolski Trustees Archive

Lucien Topolski is now in the process of reviving Feliks Topolski’s studio and archive, preserving for a new generation his grandfather’s prolific work as chronicler of the 20th Century.

Following a period of dormancy, the studio is returning to its function as an educational charity promoting Feliks Topolski’s works. It is open to students, historians and archivists studying the range of Feliks Topolski’s artwork and the plethora of themes, events and individuals addressed within it. The studio also houses the large majority of Feliks Topolski’s Memoir of the Century, some of which hangs in the nearby Topolski bar under the arches of Hungerford Bridge on the Southbank where it originally stood.

Lucien studied History BA, before continuing to focus on Medieval History at M.Phil., both at Trinity College, Dublin. Aside from his work with the studio, Lucien researches and writes a historical film.