Natalia Puchalska in Conversation with Patrick Baty

NP: What is your earliest memory related to Poland and its culture?

PB: Poland came up in snippets of conversation throughout my childhood although, in retrospect, my grandmother Edith who was half Polish rarely mentioned it. I think that the family felt that because Stanisława de Karłowska, her mother, had been in England since the 1890s and because there was no surviving family or property left behind in Poland, we should concentrate on being English. We did this reasonably well, but I am incredibly proud of my Polish heritage. Many of the paintings that covered the walls of our house were of Polish scenes, and the family homes at Wszeliwy, Mydłowiec and Kościelna Wieś were vaguely familiar in spite of not having set foot in them. Other memories are fragmentary and include such things as the smell of dill in my grandmother’s cooking and my father’s own memory of having visited Poland in 1936 and being met at the station by the same coach and horses that appeared in one of his grandfather’s pictures.

Patrick Baty; photo courtesy of Thames & Hudson

The Carosse by Robert Bevan

When slightly older I do remember how upset my grandmother was when Louis FitzGibbon’s book on Katyń was published in 1971. However, the details were never mentioned, and it is only recently that I have learnt how much the family was affected by the war.

NP: The painter Stanisława de Karłowska was your great-grandmother. Can you recall any family stories concerning her life?

PB: As a boy I remember the story about her smuggling two revolvers into Poland for the protection of her two sisters who were living there. This must have been just after the First World War. I remember hearing that my great-grandparents had met in Jersey, at a wedding, and that it was clearly love at first sight. After a series of passionate letters in French, the only language that they had in common, Robert Bevan travelled from Sussex to Poland to ask her father for his permission to marry her. He arrived on horseback, unannounced, knowing only the name of the village where she lived. The story still brings a lump to my throat. During the war she came to live with my grandparents, in Chester, and had to be issued with a pass by the Chief Constable so that she might continue painting in public without being arrested as a possible spy – she retained a strong foreign accent for the whole of her life in England.

NP: In one of your talks about Stanisława de Karłowska, you mentioned her family’s commitment to the Polish cause, e.g. her father took part in the January Uprising. Did Stanisława cultivate these patriotic traditions while living in London? Did she have any family souvenirs related to the patriotic past of the Karłowski family? Can you tell us more about these objects?

During the First World War she and Robert were very active on behalf of Polish refugees, and they set up the Polish Refugee Fund, which later merged with the Polish Victims’ Relief Fund. During the Second World War her daughter, Edith, worked on behalf of the Polish refugees and I remember hearing how distressed my grandfather was to learn that some of his suits, including his evening tails had been donated to the cause. In 1944 she became Sheriff of Chester and built a strong relationship with the Polish airmen at nearby RAF Sealand. This resulted in a carved stone tablet which was unveiled on July 27, 1944 (and which has recently been commemorated).

I understand that she later became involved with the governance of the Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum. She was awarded the Gold Cross of Merit for her work in furthering Polish interests in the UK – I now have her medal. I also have a ring that dates from the Third Partition of Poland of 1795. This consist of a gold and enamelled coffin. When one presses a shield at one end the lid lifts and the figure of a Polish knight rises. I also have a silver symbol of the Polish–Lithuanian–Ruthenian Commonwealth and a Polish eagle – all were in my grandmother’s jewellery case.

Ring dating back to the Third Partition of Poland of 1795 featuring a gold and enamelled coffin and a rising Polish knight

NP: Works by Stanisława de Karłowska are part of many national and regional collections in the UK. Is there any specific painting by your great-grandmother you particularly like or find important? And why?

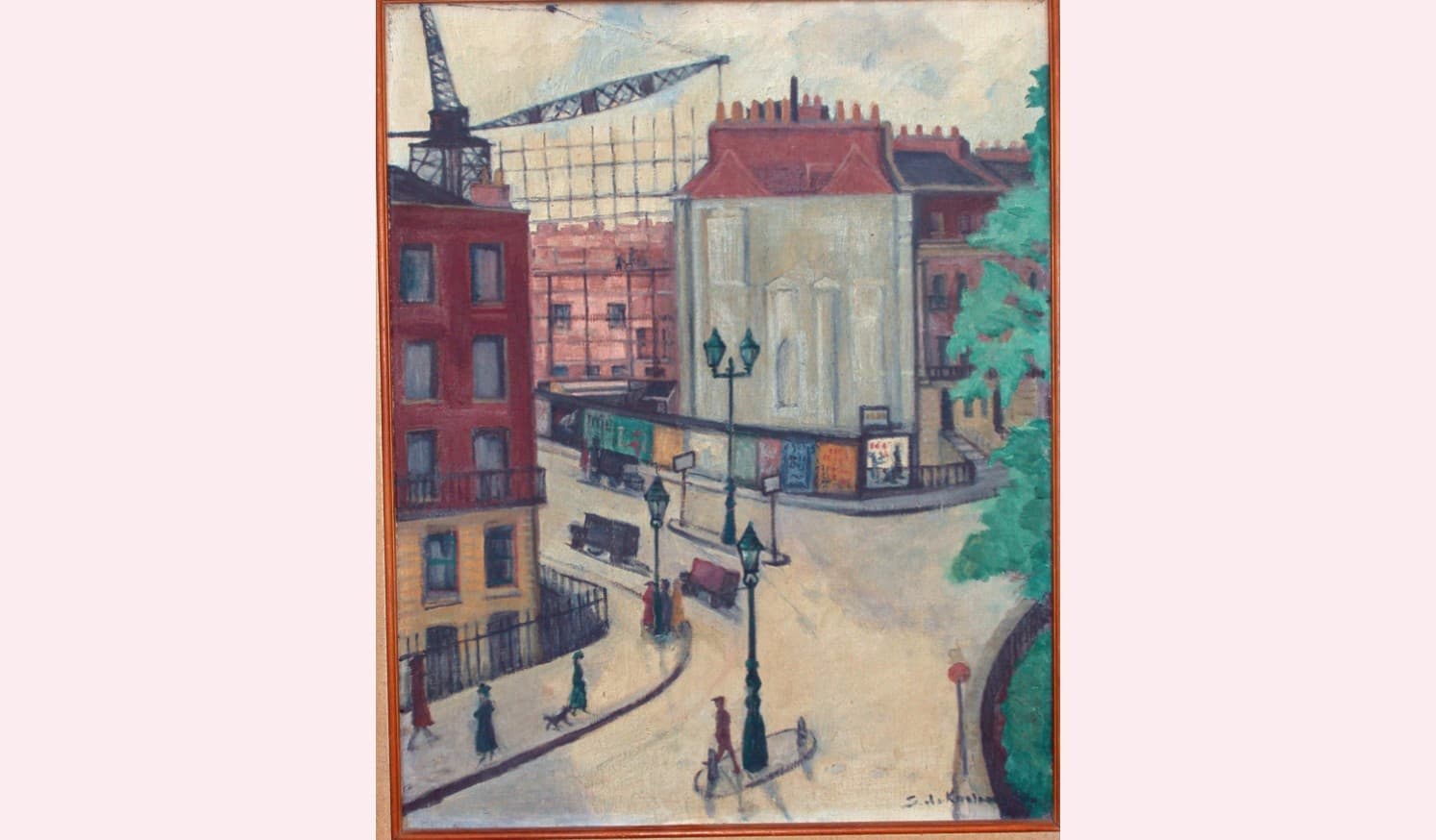

PB: I am very fond of Russell Square. It is one of many scenes of London and dates from about 1935. It shows some people and a couple of rather curious vehicles at the Junction of Montague Place and Russell Square, London. In the background is the scaffolding around the partly built Senate House, which was completed a couple of years later. She has also managed to introduce an advertising poster for Guinness on the hoardings. This shows the famous sea lion and the ‘My Goodness My Guinness’ caption which had been the work of her son Bobby, who ran the Guinness account for his advertising company, S.H. Benson. Karłowska lived at No 36 Russell Square from 1936 and the painting was probably made from an upstairs window.

Russell Square by Stanisława de Karłowska, c.1935

‘My Goodness My Guinness’ advertising slogan by the copy-writer R. A. Bevan (aka Bobby), son of the painter Robert Bevan, for the advertising agency S. H. Benson

NP: For those who have not yet heard about de Karłowska, how would you summarise her cultural significance for Britain, and her key achievements?

I think that she was most significant as a female artist who played an active part in the London art world in the early 20th century. She exhibited with the NEAC and the Women’s International Art Club, and from its foundation in 1912 with the London Group, as a full member. She also entered paintings for mixed showings at such venues as Olympia [Daily Express Women’s Art Exhibition, July 1922], Allied Artists Association and the Cooling, Grosvenor and Leicester galleries in addition to the Cumberland Market Group. Others have said that her work combined a modernist style with elements of Polish folk art and that what she ‘has to say she tells us lucidly in pure and harmonious colour.’ During her husband’s lifetime she tended to follow him stylistically and their palettes were very similar. However, from the early 1930s she adopted a simple style, following no particular painter.

NP: Despite being a woman artist at the beginning of the twentieth century, the time when women were denied taking an active part in public life, Stanisława was a prolific member of many artistic groups, such as the London Group. She would frequent fashionable cafes – hubs for London’s intellectual circles and became a muse for artists such as Harold Gilman or her husband, Robert Bevan. Would you agree with the statement that she was a truly modern and cosmopolitan artist?

She trained in Kraków and Paris and met many artists, poets and writers in London, aformed a number of close friendships with them. Like her husband and their colleagues in the Camden Town Group she drew inspiration from the everyday. Two such scenes of hers can be found in the Tate Gallery – The Fried Fish Shop and Swiss Cottage. Their circle comprised the sort of artists ‘to find beauty in the commonplace and romance in the familiar’. She subscribed to the belief that painting in a simple style could produce a ‘greater truth to nature as well as for decorative effect’. Whether streetscapes in north London, or landscapes in Poland, Brittany or Devon she was just as comfortable painting portraits or still lifes. She was also an accomplished printmaker and exhibited with the Society of Wood Engravers throughout the 1920s.

NP: You acted as a consultant on many major restoration projects in the United Kingdom, and in the 1980s produced a range of paint colours based on those offered by a Scottish housepainter in 1807, which initiated the present wave of historically-themed paint ranges which are still popular today. In April 2000, Homes & Gardens described you as being ‘Undoubtedly the most influential of our (paint) experts…whose breadth and depth of knowledge is unrivalled’. What made you choose your career path? Was it due to your family’s artistic background?

When I left the Army, I quickly realised that the only thing about which I had limited knowledge was fine art. I also had a strong interest in architecture. Having worked briefly for a London art gallery I then joined my father, who had set up a shop in 1960 specialising in paint colour – Papers and Paints, in Chelsea. He certainly had an eye for colour and taught me the technicalities of colour-matching. I suppose that having grown up surrounded by works of art gave both of us a good grounding in the appreciation of colour. Robert Bevan, himself, had been described as ‘perhaps the first Englishman to use pure colour in the 20th Century’ so colour had always been in the background.

For more information about Stanisława de Karłowska, read https://anglopolishculturalexchange.org.uk/anglo-polish-research/on-stanislawa-de-karlowska-by-natalia-puchalska/

The conversation with Patrick Baty took place on 9th October 2022

Patrick Baty has an artistic background. Two great-grandparents were the artists Robert Bevan and Stanisława de Karłowska. Since leaving the Army he has pursued a career in the decoration of historic buildings. His work covers research, paint analysis, colour and technical advice. Projects have ranged from King Henry VIII’s heraldic Beasts and London social housing estates to major structures such as Tower Bridge. He lectures on a variety of subjects and has written numerous articles and two books – The Anatomy of Colour and Nature’s Palette, both published by Thames & Hudson. Patrick has co-curated several exhibitions and is currently researching the artist members of that extraordinary regiment – The Artists Rifles. He and his wife run the family business Papers and Paints, in Chelsea.

Natalia J. Puchalska is an art historian with a keen interest in Central and Eastern European art from the 20th century and beyond. She holds an MA in Art History from the University of Sussex and a BA in the same subject from the University of Gdańsk, Poland. She works as Head of Communications, Literature and Education at the Polish Cultural Institute in London, where she has been involved in many interdisciplinary projects, such as the Conversations with God: Jan Matejko’s Copernicus exhibition at the National Gallery in London.